Our clients have lived on this plot of forest and farm for over ten years, always intending at some point to replace the existing, poorly constructed 1992 house with a new energy efficient home. The acreage includes about 80% sustainably managed forest, and 20% pastureland and farm. Our clients grow and process a majority of their own vegetables and fruit, and eat only wild meat. (We have been served venison pizza and moose chili at design meetings!) They intend to live on this land, in this home, for the rest of their lives. Our clients approached us with the intention of building a net-zero energy home. I was in the midst of the Passive House Consultant Training at the time, and suggested we try that path instead.

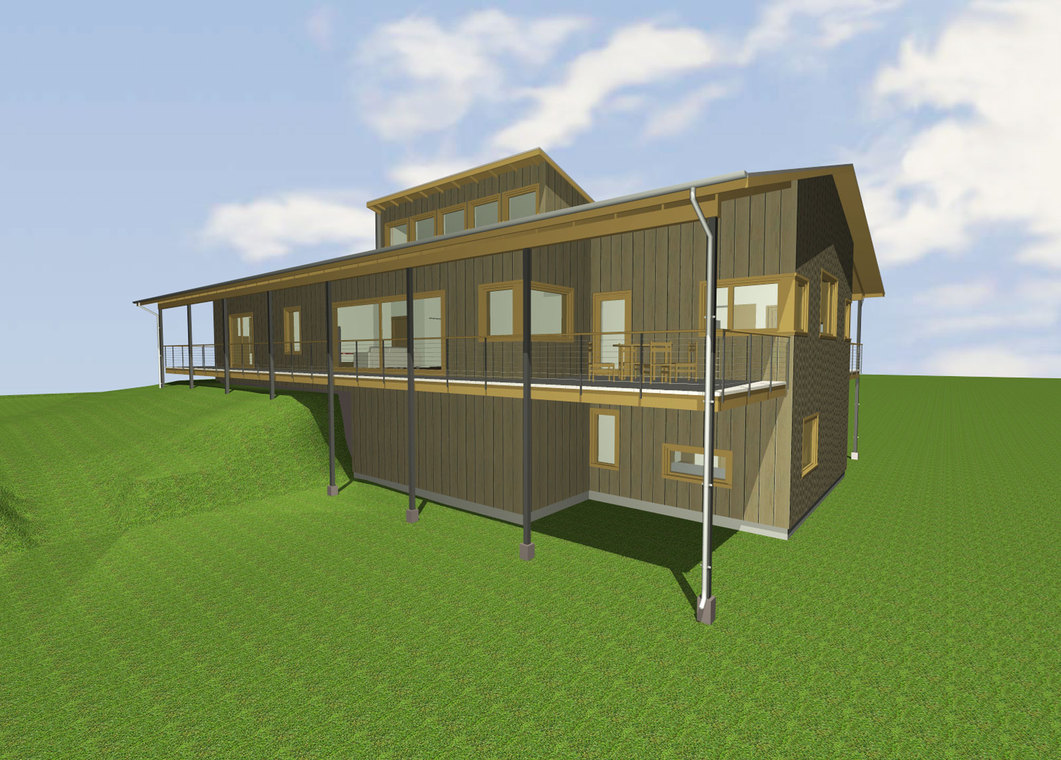

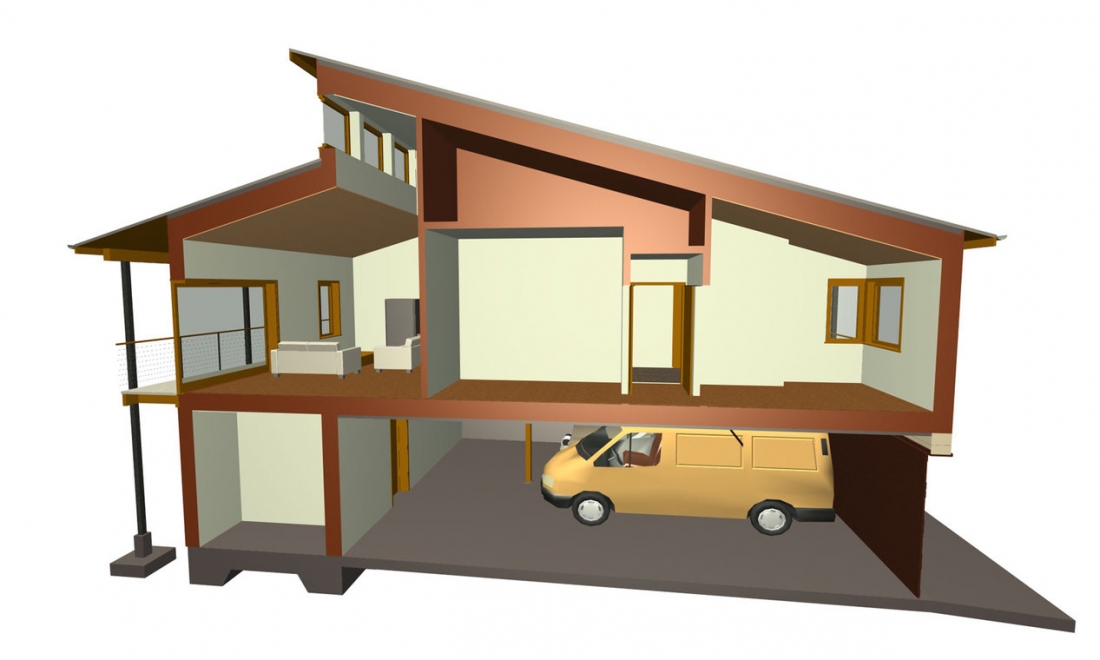

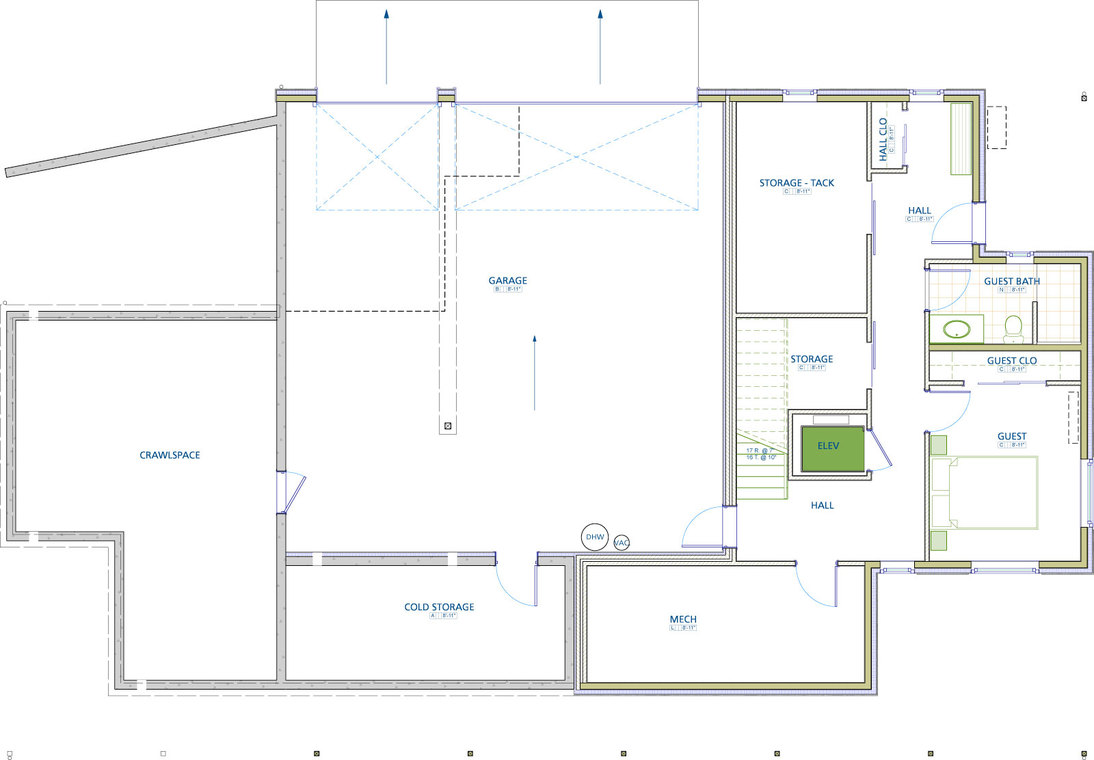

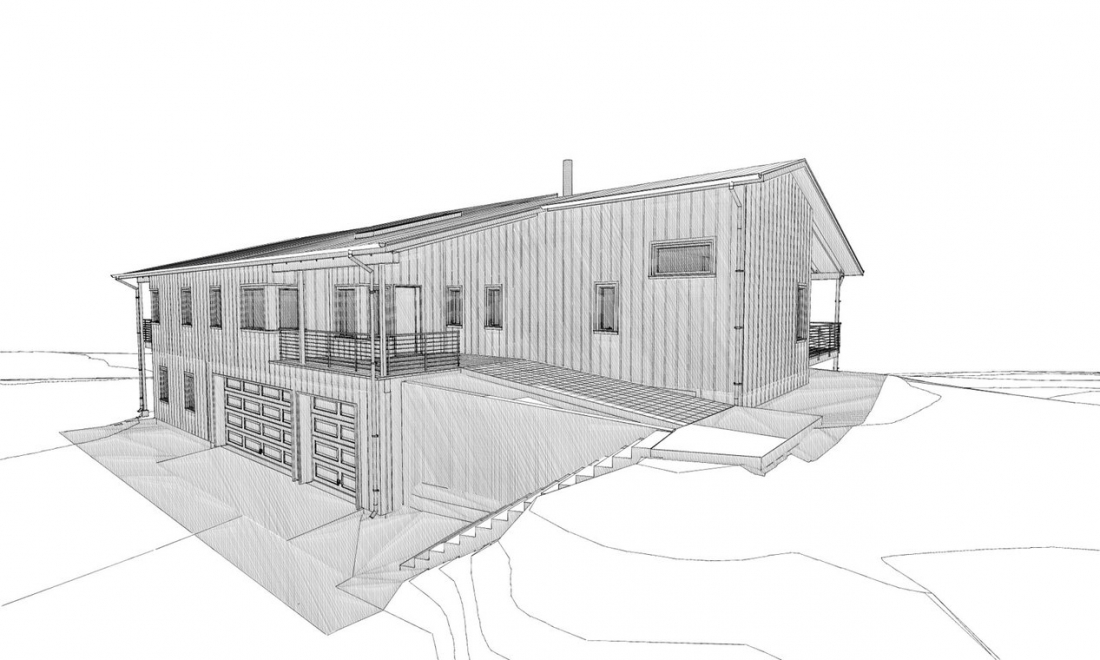

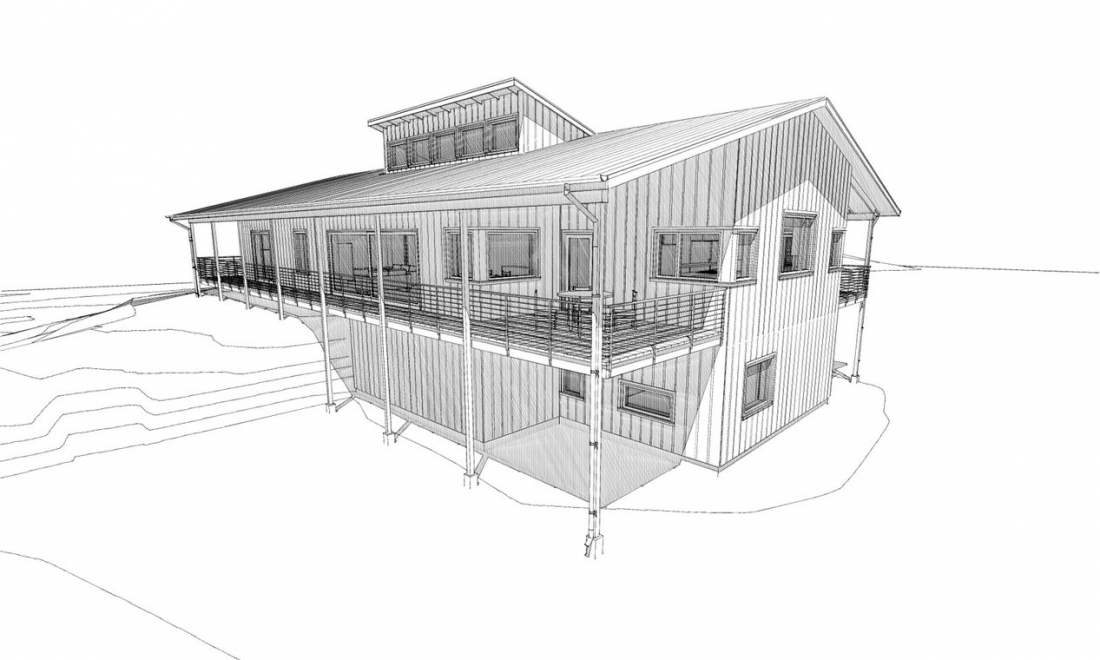

The design of the house was inspired by a traditional Australian farmhouse type called a “Queenslander,” and in fact one particularly lovely Queenslander I visited while in Australia visting my wife’s family in 2004. (See photo below.) The main living floor of a Queenslander is raised a story off the ground (above snakes and overflowing rivers), and often surrounded by wide verandas. The lower floor remains open, and is used as a shaded play area for kids, space for parking vehicles, and other utility areas. Having lived in Australia, our clients were open to this notion. This arrangement dovetailes nicely with the way they want to inhabit the site. (After a day of working on the farm, they said, the last thing they want to do is “bring the outside in.”) The existing house has a similar arrangement, and like the new house, sits partially on a small hillock.

The house’s style is functional farm. We aspire to make it as authentic as its owners. Slender steel posts support the verandas as they would on a Queenslander. Siding is fiber-cement board and batten, to match the barn. Roofing is metal standing seam. Interior finishes are unpretentious—myrtle wood, ceramic tile and Marmoleum floors for example.

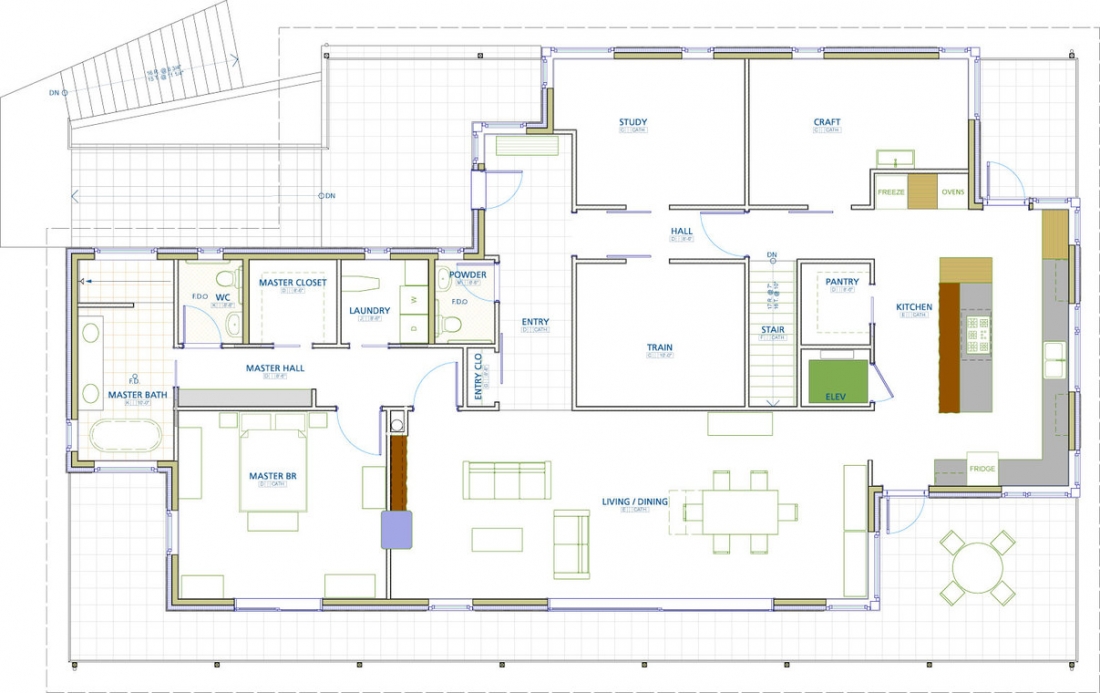

The long axis of the house runs east-west, affording both the desired solar exposure and views to the foothills to the south. The main rooms of the house run along the south side. The south veranda is like a French balcony. Opening the lift and glide doors of either the master bedroom or living room connects the room directly to the view, with minimal intervening deck in one’s visual field. It turns the room itself into a place that feels like a balcony, rather than creating a separate deck outside the room. There are deep verandas on both east and west ends of the house, outside the master bedroom and outside the kitchen, to take advantage of morning and evening light. The large, working kitchen is on the east, with a spectacular view of a nearby volcano. A central spine of utility rooms includes a room which will hold a toy train layout, a collaboration of the owners. Study and craft rooms will serve multiple production purposes, from train scenery to plant seedlings.

The clerestory (and the sixteen foot lift and slide living room door) came about after we discovered through modeling in the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) that we needed more south-facing glass. PHPP provided fantastic feedback during the design process.

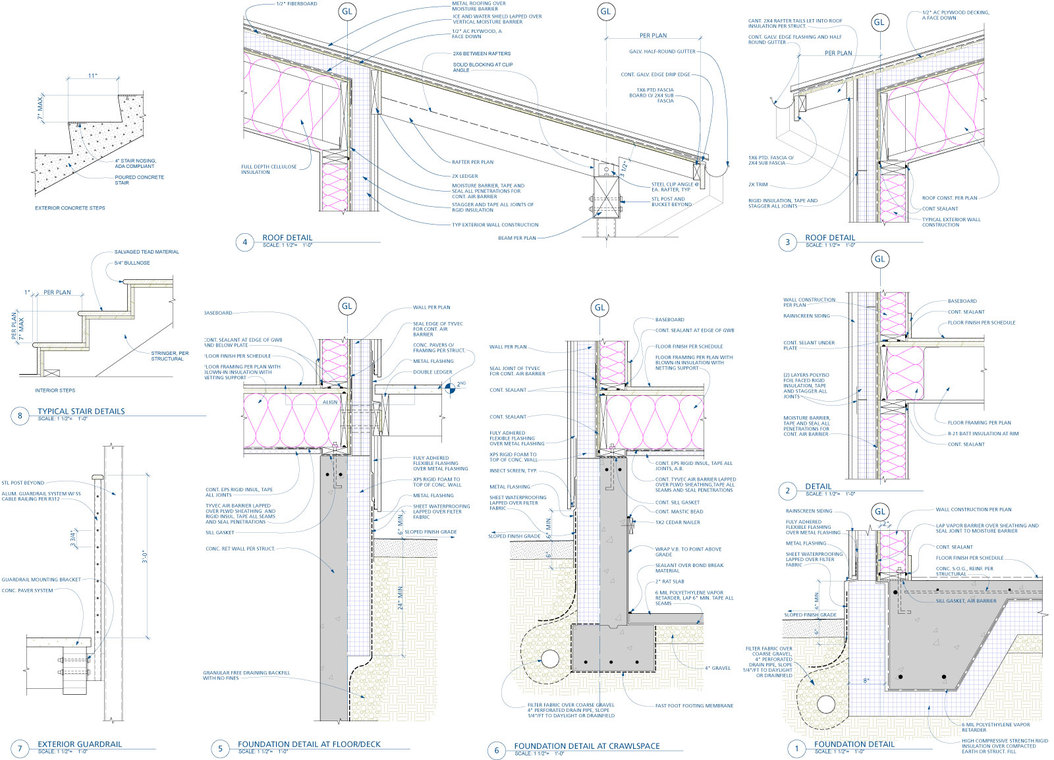

We looked at several alternatives for the exterior envelope, including Larsen trusses, a double stud wall, and autoclaved aerated concrete before settling on four inches of rigid EPS foam over a 2×6 stud wall with blown-in cellulose insulation. Since this was our first Passive House, and it is likely to be the first Passive House seen by Pierce County building officials (and by most contractors in the area) our thought was that this system would appear the simplest and most conventional of the lot, and would raise the fewest eyebrows.

At the conclusion of the Preliminary Design phase, we solicted ballpark prices from three local contractors. We set the 2009 Washington State Energy Code as the baseline, and created an add alternate for bringing the house up to Passive House standards. The baseline price included a ground source heat pump as the heating source, and an energy recovery ventilator—not uncommon components in well-crafted custom homes. The Passive House alternate included adding additional insulation at slab, floors above unheated space, walls and roofs; substituting better performing windows (lower U-value and higher solar heat gain coefficient); a requirement of meeting the air tightness standard of 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 Pascal with the building envelope. The Passive House alternate also deducted the ground source heat pump, as the heat it provided would not be necessary with the improvements in the envelope. We planned at that time to provide the small amount of additional heat required with an inline hydronic duct heater powered by solar hot water, though we switched to a mini-split air source heat pump in the end.

We were very pleased with the numbers we got for the ballpark from the three contractors. The Passive House alternate added, respectively, seven per cent, five per cent and two per cent to the construction cost of the house. Undoubtedly the final numbers will be more, as some aspects of the mechanical design, for example, have become more complex as they have been developed. Still, we hope that the numbers for the final pricing will still show Passive House adds less than a ten per cent premium to the construction cost of the house. We feel that is a bargain, in return for minimized heating energy costs for the life of the house.

Passive House is one aspect of the design of the house. Our (and our clients’) intention is that the house balance energy savings of Passive House with careful siting that maximizes spectacular views, use of found, reclaimed and salvaged materials, specifying local sources for as many materials as possible, and a concern for healthier materials and finishes, as well as the usual accommodations of individual ways of living. It is a tall order which we hope will be fulfilled when we look back on the completed house in a year or so.