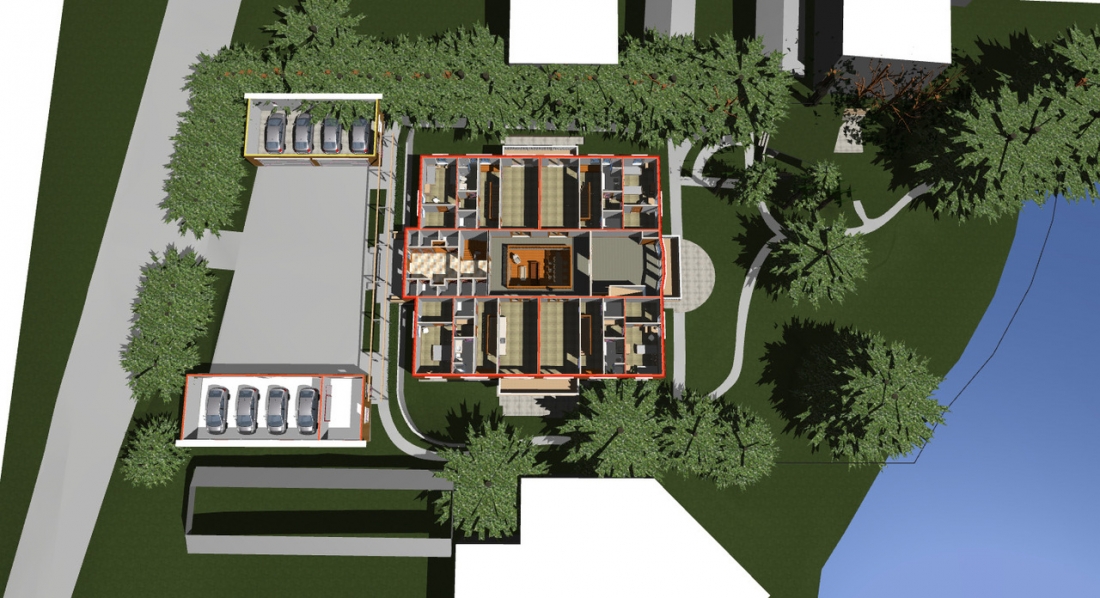

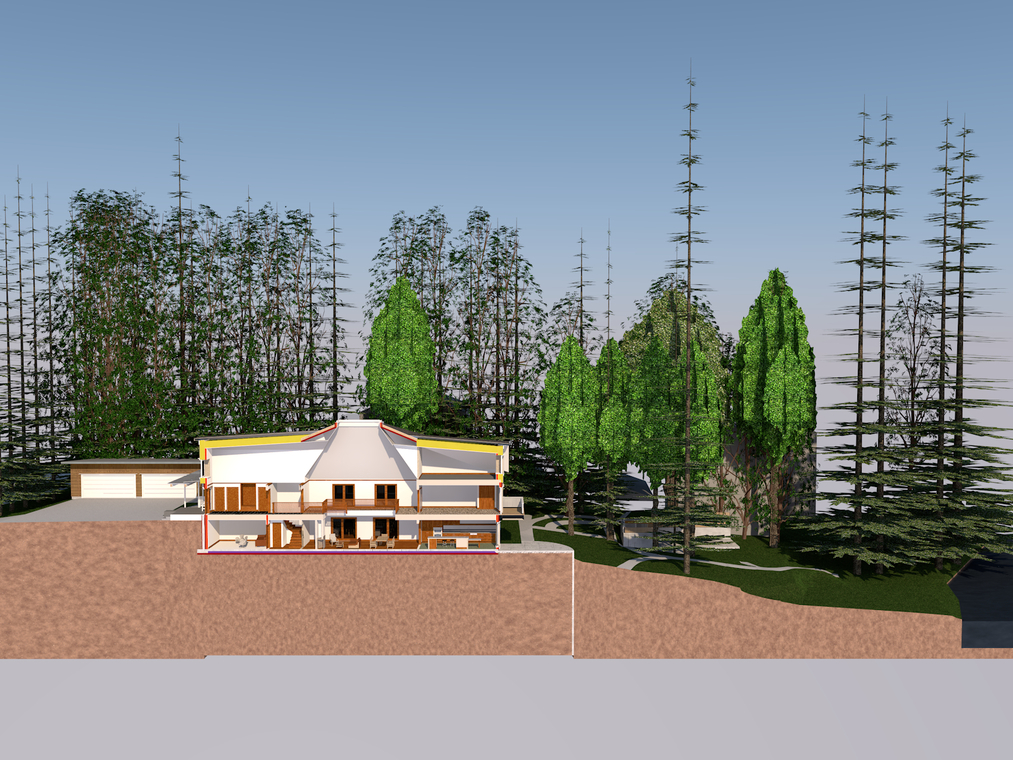

This is a design for a multigenerational home for three generations of the same family who want to live in a house together. It is designed to meet the Passivhaus standard. The house was designed to accommodate two aging parents and their three adult children as well as their partners and (so far) one grandchild, and possibly a grandmother as well. There are four suites in the house–one on each corner of the house, one for each couple. Each suite has a sitting room with a kitchenette, a bedroom, a Japanese bath and laundry downstairs, and another bedroom and a conventional bathroom upstairs. Everyone shares a large multi-cook kitchen, Great Room and Media Room on the ground floor, and a game room and multi-purpose rooms (craft, computer, kids’ play and exercise rooms) on the second floor, as well as a separate garage and shop space, and the garden. The multi-purpose rooms open onto the second floor mezzanine, and have a similiar relationship to the shared space as the sitting rooms on the ground floor.

Working with realtor Danielle Johnson, we identified a number of possible locations and reviewed them for suitablity for the project, settling on two adjacent parcels at 90th and Palatine in the Greenwood neighborhood. It was perfect (high walkscore, almost flat, reasonable price, alley access) except for the layer of peat that resides five feet down below much of the neighborhood, remnants of an ancient bog. We did a quick feasibility study which was favorable, my clients purchased the site, and we began our design.

We visited the Department of Planning and Design (now SDCI) with the Preliminary Design. A review by Zoning confirmed that the house would be considered a single-family house.

Multigenerational housng–several generations of a family living in the same house–is common in other parts of the world. This is a new building type in Seattle, though of course people have been informally living this way for…generations. Our first task was to find an architectural expression of the particular way our clients wanted to live in the house. It’s a blend of a single-family house and co-housing, with important differences. It is much smaller in scale than most co-housing, and sharing a house with your adult children and their spouses and their children suggests a different approach to privacy than living in a house with your children when they are children. Everyone wanted some degree of autonomy and privacy.

- There are eight bedrooms and one kitchen. Each suite has a wet bar, as does the Game Room.

- The house and landscape are fully accessible and adaptable, designed for aging in place. There is an elevator. My clients expect to live in the house the rest of their lives.

- The structure itself has been designed to last 100+ years.

- The house meets all of the requirements for Priority Green (Water Sense, green storm water infrastructure, recycling rate, etc) except it is larger than a typical single-family house.

- 44% of the house’s interior area is shared space. (Not counting the garages and workshop, which are shared as well.)

- Each of the four two-bedroom suites (one for each couple) are about 1,100 SF each.

- Parking provided was in excess of single-family zone requirements.

- All setbacks, height and lot coverage aspects of the design conformed to single-family zone requirements.

- The design and level of finish of the house itself is very modest. The final estimate for the house on the Greenwood site, not including sitework, was about $190 per square foot, well within the owner’s budget.

The peat beneath the surface of the site in Greenwood proved challenging. In conversations with structural engineer Carissa Farkas, civil engineer Chris Webb and pile contractor McDonnell Pile, and with analysis from a corrosion engineer, we learned that due to the acidity of the peat, steel pin piles could corrode to the point of structural uselessness in as little as nine years. We went with an auger-cast concrete pile and grade beam system, to provide a foundation that would be sure to last the 100+ year intended life of the house.

After submitting the permit application we ran into a snag with the City of Seattle. The City changed their minds about allowing the project to go ahead in a single-family zone. Despite wide-spread support—from Director of DPD Diane Sugimura, Councilmember Mike O’Brien, Kathy Nyland in the Mayor’s office, the Seattle Planning Commission and others—the internal stairs in each of the suites proved a sticking point. (A Director’s Rule from 1983 included internal stairs as one feature that defined a “dwelling unit,” so they considered the house as four “dwelling units” and therefore not allowed in a single-family zone.)

We proposed a design for the project that would have allowed it to go ahead on the Greenwood site. The simple solution was to have two one-level suites (one ground floor, one second floor) on each side of the central shared space. That would also have reduced the square footage of the project by 30%, eliminated the internal stairs, one bathroom and associated circulation space in each suite, and therefore would have substantially reduced the construction cost as well as made each suite even better for aging in place. My clients were unwilling to give up the internal stairs.

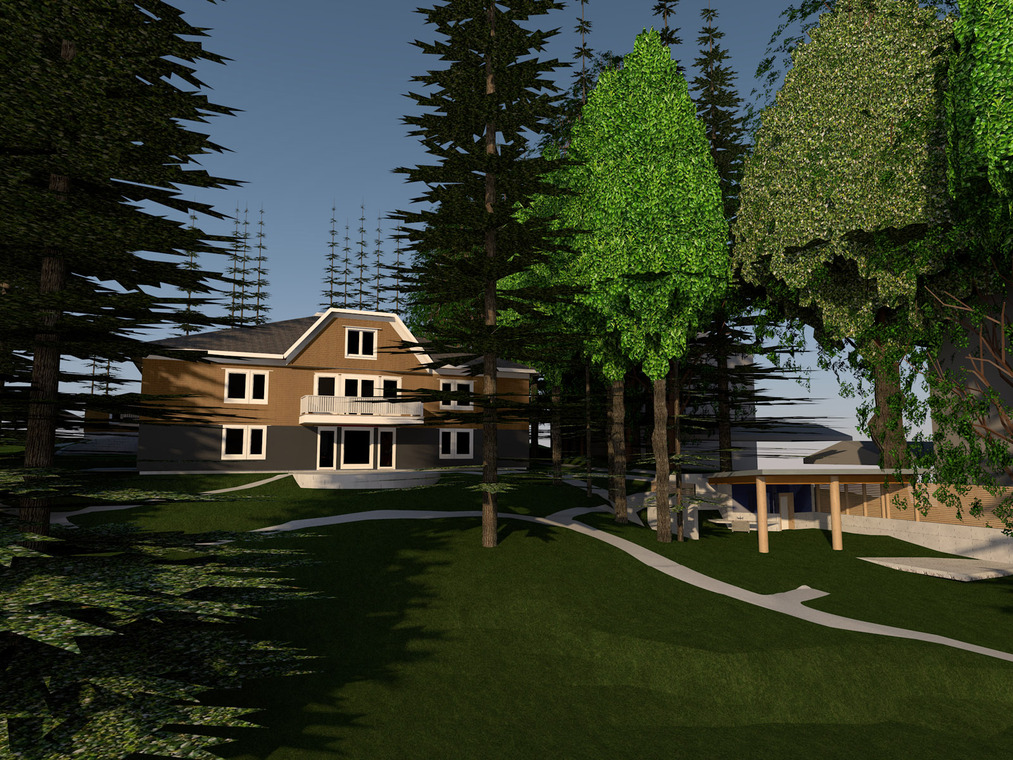

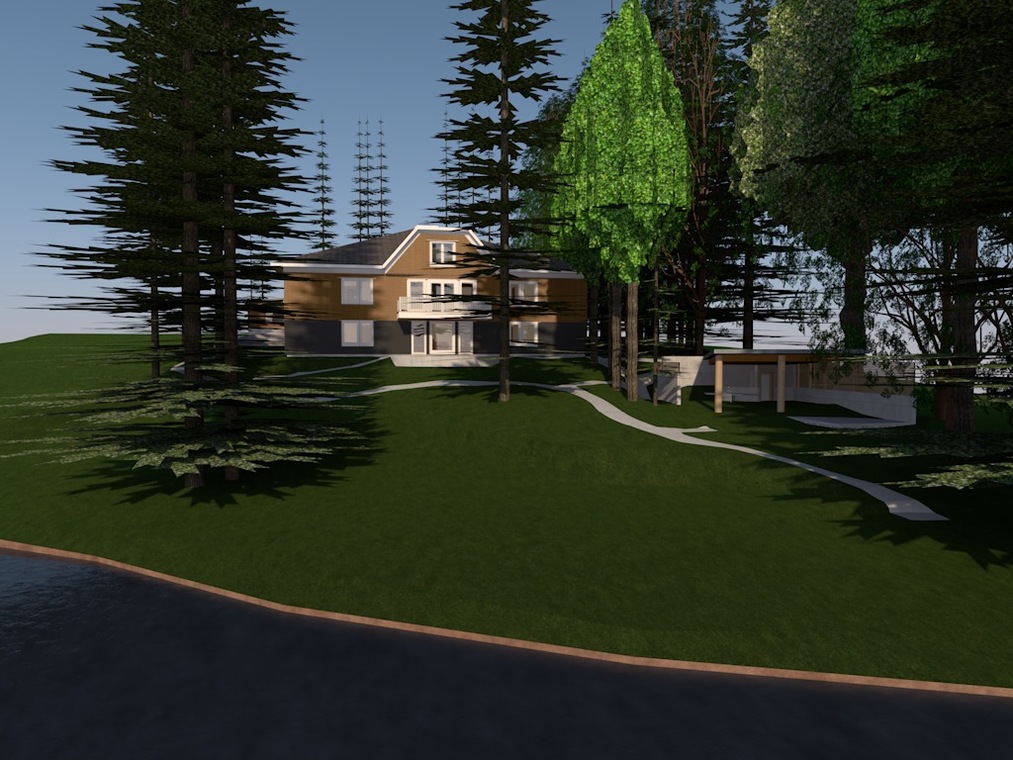

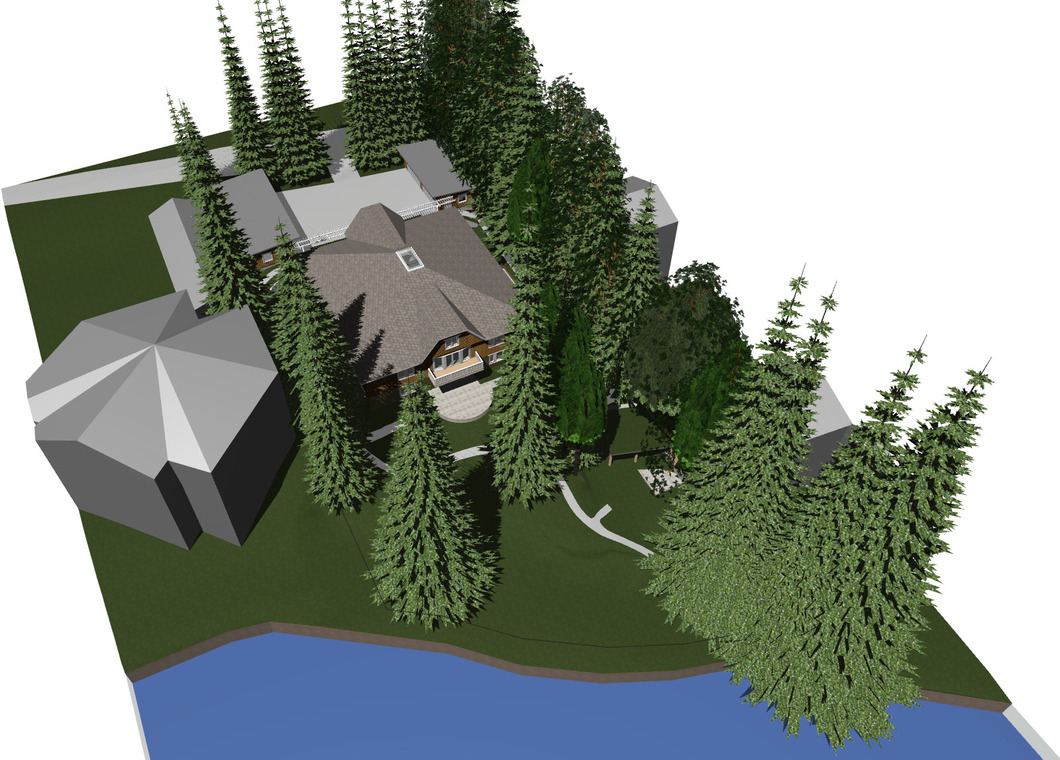

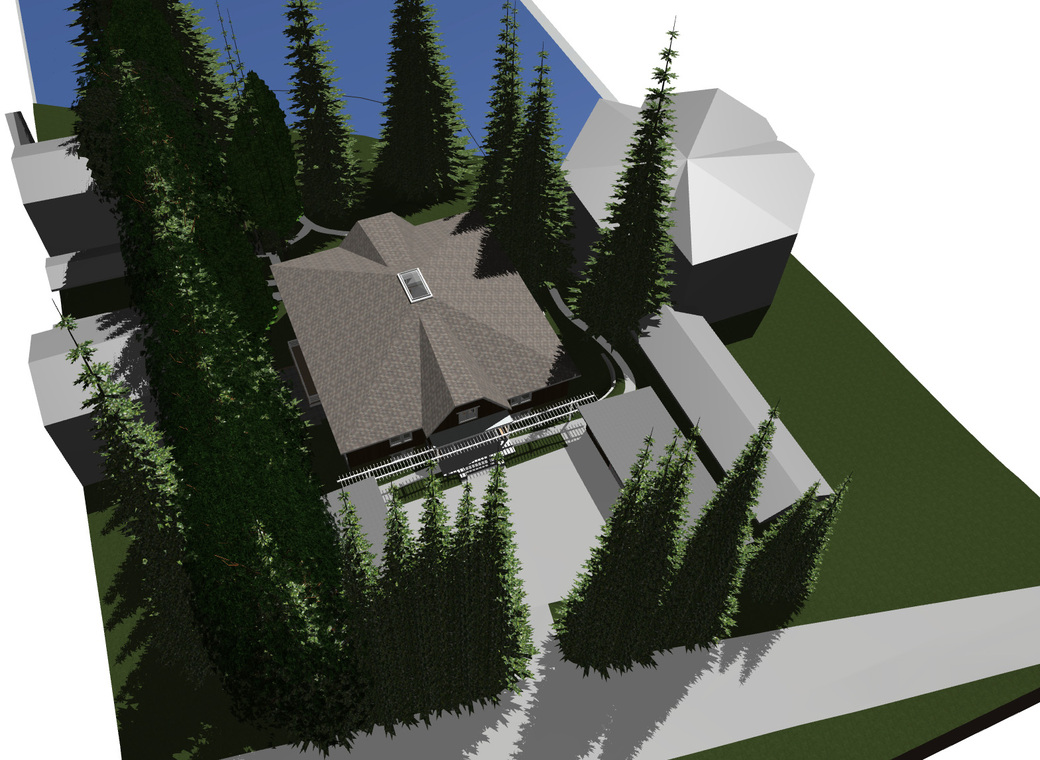

They sold the lot in Greenwood, and purchased another site in Shoreline. City of Shoreline embraced the idea, saying we could put the project on any single-family lot it would fit on in Shoreline, internal stairs or no. In the six months after my clients closed on the new property we had the site surveyed, did a study of the existing historic house, Tree Solutions catalogued and evaluated the 100+ trees, a wetland biologist did a shoreline study, we adapted the design of the multigenerational house to work with the topography and context of the complex new site, our civil engineer Chris Webb came up with a design to handle rainwater, our structural engineer Carissa redid her design, and we successfully went through a SEPA review process with the community in preparation for submitting the permit application. The contractor then took an unusually long four months to prepare a final estimate. That estimate exceeded my clients’ budget by 13%, and they abandoned this design for the project, and thus our involvement in the project ended.