Urbanists love trees. Let’s just get that out of the way at the outset. We love them for the same reasons everyone else does: the shade that cools us and the patterns leaf shadows make; their beauty, their bark and gnarled roots; the way they mark the seasons and on a longer scale the passage of time in our lives as they grow; their carbon sequestration; the way they sound as wind moves them; their fruit; the beautiful objects their wood makes. I sometimes think I can hear or feel the connection between them, Ent-like, in the forest, now documented by the work of local mycologist Paul Stamets and ecologist Suzanne Stimard among others.

I work with the best consulting arborist in Seattle, Scott Baker of Tree Solutions. He’s the tree expert who gets called in all over town when there is a particularly difficult tree preservation problem on a construction project. He knows how, if it’s going to be possible at all, to make sure construction does not adversely impact the health of a tree. If a tree can be preserved close to a new building, working with Scott, we make every effort to ensure that it remains and thrives.

I have had the pleasure and privilege of working with several brilliant landscape architects, including Linnea Ferrell and Scott Mantz. The focus of my practice for the last 25 years has been ecological architecture, and I choose to work with other professionals who share my values. I work with tree-huggers. I have been surprised at the attitudes of these professionals who know a lot more about trees than I do. They do not hesitate to remove a tree where it interferes with the layout of a new building or planned use of a landscape. Building a building around a tree, it turns out, is more a conceit of architects than the people who know trees intimately and work with them on a daily basis.

When it comes down to it, I believe creating a new Passivhaus building—ideally making homes for several or even many households on one lot—takes precedence over retaining existing trees on a parcel. There are all sorts of environmental reasons this is a big picture wise and good choice. People living in cities use less energy, and so emit less CO2 than people living in the suburbs. Multifamily buildings use less energy than single-family houses. Building so more people can live closer together makes it easier for them to walk and ride bikes instead of driving. Building in the city means, for a given population, fewer trees are cut down in suburban areas, and less farmland is converted to subdivision. On my projects, the layout of a building that we hope will last at least a century will win out over keeping all of the existing trees. In that time, the new trees we plant will grow as big and tall as the ones we have reluctantly removed.

Like everyone else, urbanists want more trees planted, and whenever possible, we like to keep the big old ones we already have. There’s the rub. Sometimes trees are in the way. If they can’t be worked around, sometimes they have to be removed to make room for new places for people to live.

We want more trees…AND we want more houses, in the same city. What is a responsible urbanist to do? We know that retaining trees on private land is problematic. Single family zones are losing tree canopy at a greater rate than multifamily zones, and currently about two-thirds of land in Seattle is dedicated to single-family zoning. The proposed tree preservation ordinance will be expensive and time-consuming for everyone involved—single-family homeowners who’d like to add a backyard cottage and people building housing in urban villages alike.

Therefore, instead, we propose Intersection Trees.

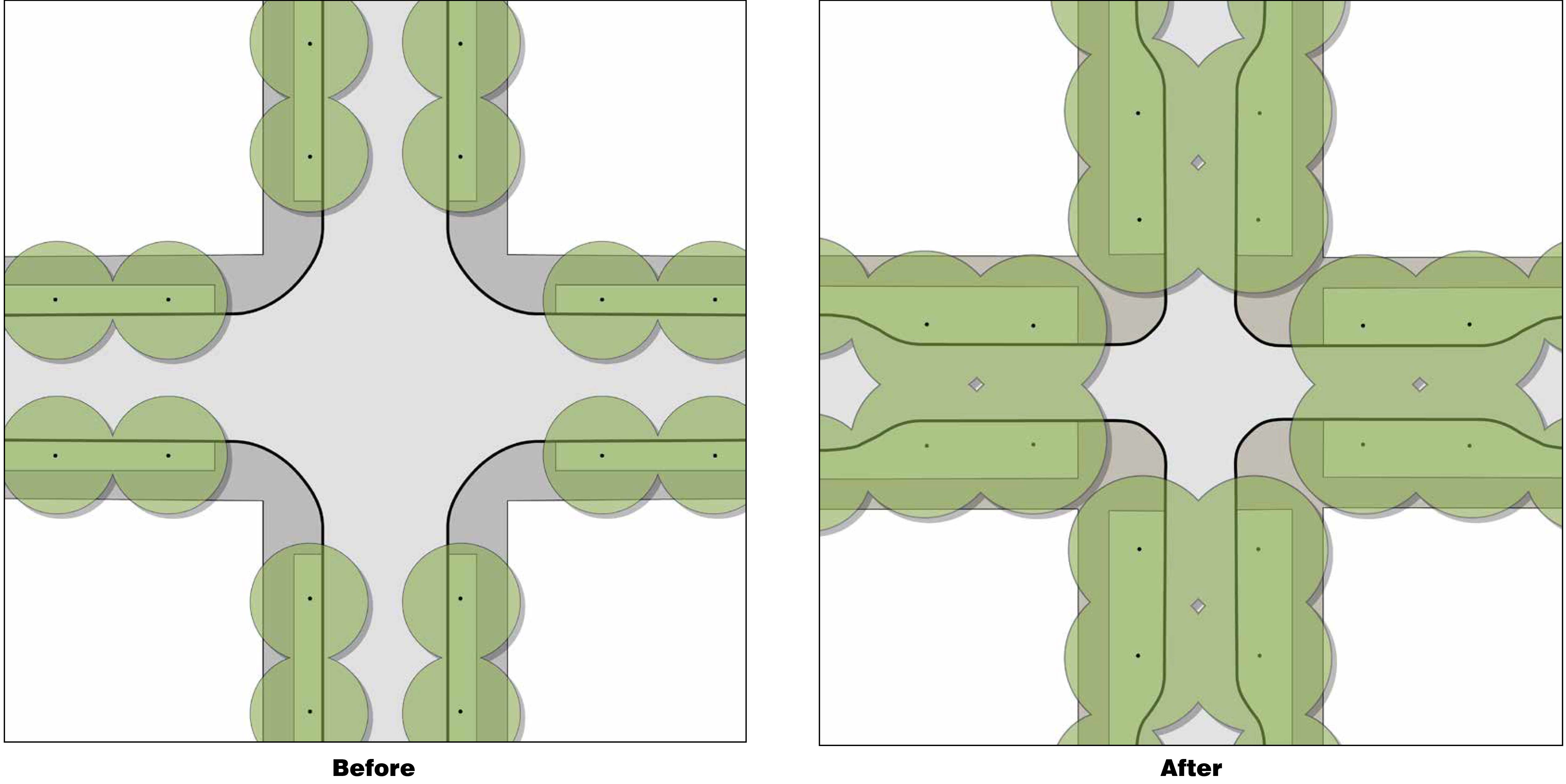

At intersections of Neighborhood Yield streets (low speed, low volume streets per Seattle Streets Illustrated) we narrow the pavement and expand the parking strip by including the typical seven-foot wide “flex zone” in the parking strip, retaining the standard eleven-foot travel lane. This narrows the crossing (good for pedestrians). It also creates space for raingardens on each corner, a Green Stormwater Infrastructure approach to filtering run-of from roads that filters run-off and protects salmon and orcas in the Sound. We reduce the radius of the curb to ten feet, the standard for Neighborhood Yield streets. Reducing turning radius of curbs is a common traffic-calming approach that slows down turning cars. By doing this, and losing one on-street parking space for each side of the street on all four corners, we can create room for sixteen new trees at each intersection. Per SDOT there are about 15,000 intersections in Seattle, I’m guessing an estimated 10,000 intersections in single-family zoned areas. (More GIS work would be needed to really quantify the number of places where this could be done.) 10,000 intersections times sixteen trees = 160,000 new trees on protected public land! Bonus: calmer traffic and a cleaner Puget Sound!

Behold:

(Click the image to enlarge it.)

Image credit: Brice Maryman

Pingback: No, Seattle’s Growth Boom Is Not a Tree Apocalypse - Sightline Institute